By Dr Holly Sutton, Vet and CEO Vetfit

Fareham, UK

Created 1212 days ago

Is it money well spent? Breaking the taboo on the cost of mental health interventions

Do we truly understand the cost implications of poor mental health in the workplace? Do we understand the return on investment for providing mental health and wellbeing support? In this article we tie together statistics from the veterinary community and the wider UK workforce, to help piece together an economic analysis. It’s time to break the taboo on the cost of mental health intervention and invest in our teams to help our profession thrive.

The people cost of poor mental health

In a profession where poor mental health feels like a continuous battle, and recruitment and retention are at an all-time low, we are struggling to retain even the freshest minds. 45% of vets who left the RCVS register last year had been practicing for 4 years or less[1].

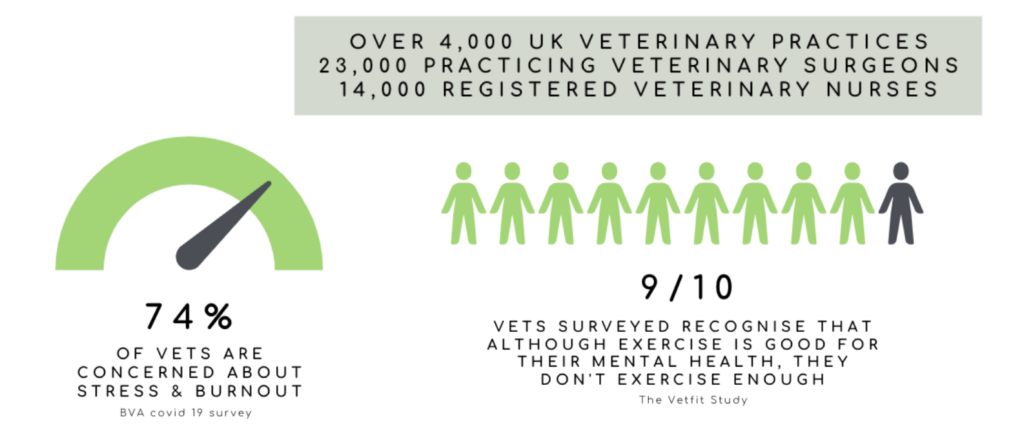

In the UK alone, there are over 4,000 veterinary practices, 23,000 practicing Veterinary Surgeons, and 14,000 Registered Veterinary Nurses. In the BVA’s Covid-19 survey, 74% of vets were concerned about stress and burnout[2]. That’s over 17,000 members of our profession.

Positive sustainable change is needed now to support the mental health of our people to break out of this vicious circle.

The prevalence of poor mental health

It is reported that 1 in 6.8 people experience mental health problems in the workplace[3]. YouGov survey data suggests the three main causes to be; too much pressure, workload impacting on ability to take leave, and lack of support[4].

Specific to the veterinary industry, we also report work intensity (pace and volume), duration of working hours, feelings of undervalue by senior staff and/or management, and performance anxiety as being commonly attributed to psychological distress[5]. Interestingly, 41% of employees experiencing a mental health problem in 2019 reported no changes or action taken in the workplace, and 70% of managers said there are barriers to them providing mental health support5 . This data suggests we know these problems exist, yet our leaders do not have the capacity to action support and positive change.

The economic cost of poor mental health

Each year, mental health costs UK employers £45 billion[6]. In 2015, mental health related issues lead to approximately 17.6 million days sick leave, or 12.7% of the total sick leave days taken in the UK[7]. It’s interesting, yet unsurprising to know that 95% of employees calling in sick with stress call in with a different problem[8], and so that 12.7%, is likely to be much higher. For example, in 2019 half of days taken off sick were thought to be due to stress[9]. Yet this figure only represents cases of absenteeism. Presenteeism (the act of being at work but not at full productivity), costs businesses 10x more than absenteeism[10].

Workplace interventions to improve mental health

The use of health programme interventions are widely used in other sectors to support employees, enhance performance and drive business growth.

In a survey by Virgin Pulse, employees took an average of 4 days off sick per year, in contrast to 57.5 days per employee lost on the job due to presenteeism.[11] In this survey, participants had completed a 12-month virtual wellbeing programme which led to improvements in sleep, stress, happiness, and yep, you guessed it; decreased presenteeism rates.

London Underground found that their greatest area of sickness absence was due to stress, anxiety, depression, and musculoskeletal disorders. In 2004 they ringfenced funding for a proactive stress reduction programme, as well as counselling programme, back pain programme, and annual health fairs. In the first 2 years of operation, the company avoided costs of employee absence of more than £500,000, yielding a positive return on investment. They rolled out the programme across the entire Transport for London workforce due to its success.[12]

Similarly, in 2007, a 600 member UK company rolled out a health promotion programme for employees consisting of an online support programme, and in-person seminars and workshops focusing on wellness issues. Over a 12-month period the company saw reductions in health risk factors, monthly absenteeism days, and an increase in work performance, yielding a positive return on investment[13].

Investment in mental health by employers yields a return of £5 for every £1 spent[14], now that’s not a figure to throw under the carpet.

So if you are an employer reflecting on whether to introduce a health intervention programme at work the question is not ‘how much will it cost me?’ but ‘how much will we save in the long run?’.

A health intervention for the veterinary profession – welcome to Vetfit!

Here at Vetfit we are passionate about supporting mental and physical health in the veterinary profession through exercise, social support, personal development, and evidence based management solutions.

We wanted to see if we could replicate the positive impact that employees have gained from health intervention programmes in other industries in the veterinary profession using a focus on exercise.

Participation in regular exercise can:

- Increase self-esteem[15]

- Reduce stress and anxiety[16]

- Prevent development of mental health problems[17]

- Improve quality of life from those suffering from poor mental health[18]

- Positively impact mood[19]

- Improve physical health, such as sleep, and reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes and heart disease[20]

- Lower risk of, and treat depression[21]

Even 10 minutes of brisk walking increases mental alertness, energy and positive mood[22].

So we conducted a small pilot study of our own. Back in 2018 we provided a group of 15 non-habitual exercisers with 8 weeks of structured exercise sessions and group development coaching. Over 8 weeks, we saw significant improvements in psychological wellbeing, work life balance and physical health.[23]

The habits adopted during the exercise programme were sustainable due to these improvements still being present six months after completion. This is further evidence to support that exercise can play a vital role in providing a realistic and sustainable strategy to counteract stressors by improving psychological wellbeing, work life balance and physical health, as well as aiding the creation of social support groups in veterinary professionals.

This was back in 2018. We’re now looking forward to 2022 where we’re releasing our online Vetfit CPD Programme – a carefully curated set of CPD sessions, combined with exercise coaching from our team. The sessions will help individuals and teams reframe mindsets surrounding exercise and wellness, as well as develop positive leadership and change management strategies in order to improve workplace culture and individual mental and physical health.

The time for action is now

With a workforce on its knees, employers have a responsibility to be more proactive in supporting the mental health of their team. Box ticking wellbeing initiatives or tackling poor mental health once at breaking point is not enough.

Use of structured health programmes are a great way to create a more positive work environment and enhance wellbeing. Best of all the uplift in your team’s productivity completely offsets the investment in your people, strengthening the bottom line of your business.

If you’d like to learn more about the support programmes Vetfit can offer you and your team, please get in touch at hello@getvetfit.co.uk – we’d love to hear from you.

About the author

Holly Sutton is a 2020 graduate practicing in small animal clinics part time, and managing the Vetfit project part time. During her degree Holly developed a passion for helping improve veterinary workplace culture, focusing on individual and team wellbeing. She’s passionate about helping professionals reframe mindsets surrounding their mental and physical health, across multiple areas including exercise and social support, both across an individual and leadership level.

References

[1] RCVS, 2021. Workforce Summit 2021 – recruitment, retention and return in the veterinary profession.

[2] BCA, Covid-19 Survey, 2020

[3] Lelliott et al, (2008) Mental Health and Work

[4] Mental Health at Work 2019: Time To Take Ownership (2019) https://www.bitc.org.uk/report/mental-health-at-work-2019-time-to-take-ownership/

[5] Vetlife. 2022. Stress, Anxiety and Depression – Vetlife. [online] Available at: <https://www.vetlife.org.uk/mental-health/depression/> [Accessed 14 February 2022].

[6] Deloitte, 2020. Mental health and employers – Refreshing the case for investment. pp.1-60.

[7] (ONS (2016), UK Labour Market; July 2016)

[8] Mind, 2013. Populus interviews in England and Wales (2060 adults) https://www.mind.org.uk/news-campaigns/news/work-is-biggest-cause-of-stress-in-peoples-lives/

[9] Health and Safety Executive, Annual Statistics (October 2019).

[10] Deloitte, 2020. Mental health and employers – Refreshing the case for investment. pp.1-60.

[11] Virgin Pulse Global Challenge data. Based on the responses of 1,872 participants who took their scientifically validated survey, benchmarked against the World Health Organization ‘Health and Workplace Performance’ Questionnaire (WHO-HPQ). 2015

[12] Business in the Community (2005). London Underground. Stress Reduction Programme.

[13] Mills P, Kessler R,Cooper J, Sullivan S (2007) Impact of a health promotion program on employee health risks and work productivity.American Journal of Health Promotion 22:45–53.

[14] Deloitte, 2020. Mental health and employers – Refreshing the case for investment. pp.1-60.

[15] Alfermann, D. & Stoll, O. (2000). Effects of Physical Exercise on Self-Concept and Wellbeing. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 31, 47–65.

[16] Salmon, P. (2001). Effects of Physical Activity on Anxiety, Depression, and Sensitivity to Stress: A Unifying Theory. Clinical Psychology Review, 21 (1), 33–61.

[17] Zschucke, E., Gaudlitz, K. & Strohle, A. (2013). Exercise and Physical Activity in Mental Disorders: Clinical and Experimental Evidence. J Prev Med Public Health, 46 (1), 512–521.

[18] Alexandratos, K., Barnett, F. & Thomas, Y. (2012). The impact of exercise on the mental health and quality of life of people with severe mental illness: a critical review. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75 (2), 48–60.

[19] Penedo, F.J. & Dahn, J.R. (2005). Exercise and well-being: a review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 18 (2), 189–193.

[20] PENGPID S, PELTZER, K. (2018) Vigorous physical activity, perceived stress, sleep and mental health among university students from 23 low- and middle-income countries. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. pii: /j/ijamh.ahead-of-print/ijamh-2017-0116/ijamh-2017-0116.xml. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2017-0116

[21] Department of Health (2001). “Exercise Referral Systems: A National Quality Assurance Framework.” Available at: http://bit.ly/1N31ONs [Accessed on 04/11/15].

[22] Ekkekakis, P., Hall, E.E., Van Landuyt, L.M. & Petruzzello, S. (2000). Walking in (affective) circles: Can short walks enhance affect? Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 23 (3), 245–275.

[23] Mays, Rose, et al. (2018). The effect of an eight-week exercise programme on the psychological well-being of a group of self-selected ‘non exercising’ veterinary students.